Blog

-

Why You Can’t Trust Food Labels

In today’s world of packaged goods and supermarket aisles, food labels are treated like nutritional gospel. Calories, protein grams, vitamins, minerals—presented as precise measurements, suggesting confidence and accuracy. But here’s the truth: those numbers are estimates at best, and in many cases, they don’t tell the whole story.

The biggest reason? Nutrients don’t come from factories—they come from the soil, the water, and the sun.

Nutrients Begin in the Soil

Whether it’s a carrot or a cow, the nutritional value of food is directly tied to where and how it was grown or raised. The vitamin and mineral content of plant foods depends entirely on the nutrient makeup of the soil they grow in. Depleted soil means depleted food—regardless of what the label claims.

For example, spinach grown in one field might contain 50% more iron than spinach from another field just a few miles away. Yet, both bags on a shelf will display the same USDA nutrient panel—based on average estimates, not actual testing of that specific crop.

Labels Don’t Measure the Ecosystem

Animals raised on nutrient-rich pasture soil, exposed to sunlight, and rotating through regenerative systems produce superior meat, dairy, and eggs. Their nutrient profiles (especially omega-3s, fat-soluble vitamins like A and K2, and CLA) differ dramatically from animals raised on grain in confined systems.

Yet, both types of meat may be labeled with the same “grams of protein” or “milligrams of iron”—ignoring the bioavailability, density, and diversity of nutrients that real-world ecosystems provide.

Most Labels Are Based on Averages from the 1960s

The USDA food composition database, which informs most food labels, is built from decades-old data and averages. It doesn’t account for modern farming practices, soil degradation, seed hybridization, or regional variability. Nor does it factor in storage conditions, time-to-market, or how processing and cooking alter nutrient content.

In one landmark study, researchers found that the nutrient content of 43 crops had declined significantly between 1950 and 1999—yet food labels haven’t adjusted to reflect that loss【1】.

“Natural” and “Organic” Still Leave Questions

Even labels like “natural,” “organic,” or “grass-fed” don’t guarantee high nutrient density. Organic crops can still be grown in poor soil. Grass-fed cattle might still graze on overgrazed or nutrient-poor land. Unless you know the quality of the land, the health of the animals, and the regenerative integrity of the farm, the label is just a rough sketch.

Micronutrients Are Often Missing Entirely

Food labels focus primarily on calories, macronutrients, and a few selected vitamins and minerals. But dozens of other phytonutrients, enzymes, co-factors, and antioxidants play a critical role in human health—and they’re never listed. Many of these are influenced by things like sunlight exposure, plant stress, and soil biology, which vary from farm to farm and are never captured in a barcode.

So What Can You Trust?

Not all food is created equal. Labels can serve as a general guide, but if you truly care about nutrient density, you have to look beyond the numbers:

- Know your farmer or food source

- Understand the soil—regenerative practices matter

- Choose local and in-season whenever possible

- Prioritize how food is grown, not just what is grown

Real health comes from real food grown in real soil—not from a standardized label.

Citations

- Davis, D. R., Epp, M. D., & Riordan, H. D. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669–682.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719409 - Montgomery, D. R., & Biklé, A. (2016). The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health. W. W. Norton & Company.

- DiNicolantonio, J. J., O’Keefe, J. H., & Lucan, S. C. (2018). Nutritional deficiencies in modern soil and food: Implications for chronic disease. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 61(1), 54–57.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2018.01.003 - Bionutrient Food Association. (2020). Variability of nutrient content in carrots, spinach, and other crops.

https://bionutrient.org

-

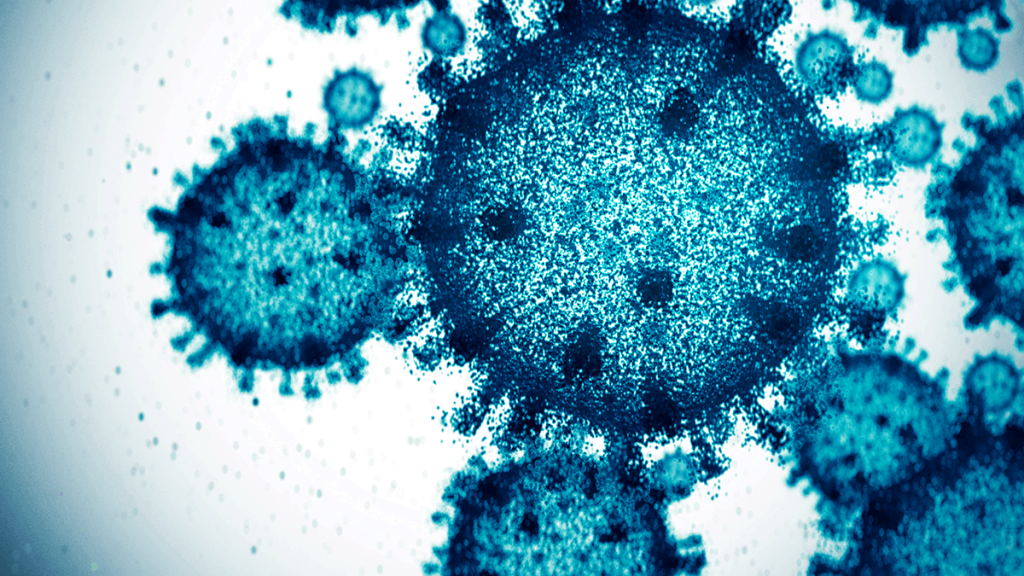

Anti-parasitic Drugs in COVID 19: Emerging Evidence from Ivermectin and Mebendazole

Early in the pandemic, tropical antiparasitic drugs like ivermectin and fenbendazole (and related mebendazole) attracted attention as potential COVID‑19 therapies. Initial lab data and anecdotal reports fueled public interest, but subsequent high-level clinical trials yielded largely negative results Fenben.pro+15Wikipedia+15PMC+15.

However, recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews are now indicating possible therapeutic benefits when antiparasitic agents are added to standard care in outpatients with mild to moderate COVID‑19.

🧠 What New Research Reveals

1. Ivermectin Meta-Analyses

A new systematic review of 33 randomized controlled trials (15,376 patients) found no overall mortality benefit, but reported reduced symptom duration and lower hospitalization rates, suggesting a subset of treated patients may have benefited .

Additionally, several earlier ivermectin studies, while not conclusive on mortality, did note modest symptom reduction and safety in mild disease

2. Mebendazole Finds a Place

An MDPI meta-analysis in Antibiotics (2025) combining ivermectin and mebendazole trials found:

- Statistically significant improvements in viral clearance time

- Mixed results on clinical recovery

- A strong safety profile MDPI

Though heterogeneity exists across studies, the combined evidence supports further investigation into mebendazole as a potential oral antiviral.

⚖️ Interpreting the Data

- Effect sizes are modest:

- Generally benefit mild to moderate cases—particularly symptom duration and possibly hospitalization risk.

- Methodological limitations remain:

- Variability in dosage, timing, and endpoints.

- Publication bias: positive results are more likely to be published.

- Safety profile is reassuring:

- Both drugs showed acceptable tolerability at standard dosages in outpatient settings

- PubMedSpringerLink+1BMJ+1.

- Both drugs showed acceptable tolerability at standard dosages in outpatient settings

👩🔬 What We Still Need

- Large, high-quality RCTs focused specifically on:

- Ivermectin monotherapy vs. placebo/control

- Mebendazole alone or in combination

- Standardized protocols:

- Clear dosing regimens

- Defined treatment windows post‑infection

- Uniform clinical endpoints (e.g., hospitalization, symptom duration)

- Mechanistic studies:

- Understanding how these drugs may inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication and whether their antiviral effect is clinically relevant.

✅ Bottom Line

- Early optimism gave way to skepticism—but new pooled data shows some promise, particularly for symptom reduction and outpatient support.

- Neither ivermectin nor mebendazole is approved for COVID‑19 treatment by regulatory bodies; decisions should be guided by evidence, not anecdote.

- Further rigorous trials are underway—and might validate the role of these readily available, low-cost medications in the outpatient management of COVID‑19.

Sources

- Satyam SM et al. (2025). Antibiotics meta-analysis on ivermectin and mebendazole RCTs

PubMedLippincott

JournalsWikipedia+2MDPI+2PMC+2

Fenben.pro. - Yengu NS et al. (2025). Systematic ivermectin review of 33 RCTs (15,376 patients) ResearchGate.

- Oxford PRINCIPLE trial (2024). Found no mortality benefit for ivermectin in vaccinated adults PHC Oxford.

- Early ivermectin studies reported modest symptomatic benefit UT Southwestern+15Wikipedia+15PHC Oxford+15.

- Observational study on mebendazole safety and hypothesis generation ClinicalTrials.gov+5PMC+5MDPI+5.

-

Giving Your Liver a Sabbath: Why Resting the Liver Is a Good Health Practice

The liver is one of the hardest-working organs in the human body. Every hour, it processes hormones, filters toxins, manages blood sugar, metabolizes nutrients, and produces bile for digestion. It is constantly active—day and night—regenerating cells, detoxifying the bloodstream, and keeping us alive.

But in a world overloaded with environmental toxins, poor sleep, overfeeding, and stress, the liver rarely gets a break. The concept of giving the liver a “Sabbath”—a regular period of intentional rest—can be a powerful, restorative health practice rooted in both physiological wisdom and biblical rhythm.

Why the Liver Needs Rest

1. Constant Exposure to Modern Stressors

The average person is exposed to hundreds of chemicals daily—from food preservatives and personal care products to medications and pollutants. All of this ends up at the liver’s doorstep. Without downtime, detox pathways can become sluggish, and liver enzymes may become dysregulated.

2. The Liver Has a Rhythm

Like every other organ, the liver follows a circadian clock. It performs certain detoxification tasks more effectively at night. When we eat late, drink alcohol before bed, or stay up past midnight, we disrupt the liver’s natural cycles and overload it during its regenerative window.

3. Overnutrition Equals Overwork

Frequent meals, excess sugar, alcohol, and refined fat consumption lead to hepatic fat accumulation (fatty liver), elevated liver enzymes, and reduced metabolic flexibility. Strategic rest from food—especially inflammatory foods—gives the liver space to repair.

What It Means to Give the Liver a Sabbath

A liver sabbath doesn’t mean complete shutdown. It means removing unnecessary burdens so the liver can catch up on repair, regeneration, and detoxification. This practice is not about starvation or extreme fasting, but about intentional rhythmic restoration.

How to Rest the Liver

1. Implement Intermittent Fasting or Time-Restricted Eating

Allowing the liver 12–16 hours without food improves insulin sensitivity, stimulates autophagy, and allows liver enzymes to recalibrate. This also lowers liver fat and reduces oxidative stress.

- Example: Stop eating by 7:00 p.m., don’t eat again until 11:00 a.m. the next day.

2. Eliminate Alcohol for a Period of Time

Even moderate alcohol use demands significant energy from the liver to neutralize. Alcohol breaks the liver’s healing rhythm and promotes fat accumulation.

- Try a 30-day alcohol sabbath to reduce liver inflammation and enzyme load.

3. Cut Sugar, Seed Oils, and Processed Foods

These foods contribute to fatty liver disease, poor bile flow, and increased oxidative burden. Whole foods—especially cruciferous vegetables—support liver phase 1 and 2 detox pathways.

- Focus on beets, broccoli, dandelion greens, garlic, turmeric, and lemon water.

4. Support Bile Flow and Detoxification

The liver detoxifies through bile production. If bile becomes stagnant, toxins recirculate. Bitter foods and hydration support this process.

- Add apple cider vinegar, ginger tea, and bitter greens like arugula and chicory.

5. Prioritize Sleep and Circadian Alignment

The liver’s most active detox window is between 11:00 p.m. and 3:00 a.m. Getting to bed early and sleeping deeply allows phase 1 and 2 detox enzymes to perform their full cycle.

- Sleep in a dark room, avoid blue light after 8:00 p.m., and finish meals at least 3 hours before bed.

6. Consider a One-Day Weekly Fast or Simplified Diet

Giving the liver one “day off” per week—such

-

40-Yard Dash – The Essentials: Max Velocity

Max velocity is the peak phase of sprinting, where the athlete achieves their highest speed. In the 40-yard dash, this phase typically occurs between 20–40 yards, depending on the athlete’s skill and efficiency in acceleration.

While acceleration builds momentum, max velocity is about maintaining posture, rhythm, and force application under high speed. It’s not just about going fast—it’s about staying fast without breaking down.

Why Max Velocity Matters in the 40

Most athletes spend too much time trying to “power through” the entire sprint. In reality, once max velocity is reached, the key is minimizing deceleration and maintaining mechanical efficiency.

Done correctly, max velocity:

- Enhances overall 40 time through efficient stride frequency and length

- Reduces injury risk from overstriding or collapsing posture

- Transfers into sport by improving top-end chase, separation, and recovery speed

Key Components of Max Velocity Mechanics

1. Upright Posture

At max velocity, the torso should be tall and stacked—hips under shoulders, chin level, eyes forward. No arching, no reaching. Postural control is critical.

2. Front-Side Mechanics

The majority of the sprint action now happens in front of the body. Knees drive up, thighs lift to parallel or slightly above, and the heel recovers under the hamstring.

Efficient sprinters spend more time in front-side mechanics and minimize backside drag.

3. Ground Contact and Flight Time

Ground contact becomes extremely short (as low as 0.08–0.10 seconds), while air time increases. The athlete is essentially bouncing across the ground with precision.

4. Foot Strike Position

Feet strike directly under the hips. Contact is quick, light, and elastic, like a spring. Overstriding or heel striking at this phase drastically reduces speed and increases risk.

5. Arm Action

Arms remain compact, rhythmic, and aggressive. Elbows drive from the shoulders, with hands moving from cheek to hip. Loose arms lead to wasted motion.

Common Max Velocity Errors

- Overstriding (trying to open up too much)

- Upright posture too early or too late

- Excessive backside mechanics (low heel recovery, extended trail leg)

- Collapsing at the hips or trunk under fatigue

- Arms swinging across the body

Training Max Velocity

Top-end speed must be trained with intentional drills and rest intervals to maintain high quality. Include:

- Flying sprints (e.g., 10–20 yard buildups into 10–20 yard sprints)

- Sprint-float-sprint or sprint-float-sprint-float sequences

- A-skip and B-skip progressions

- High-speed bounding and straight-leg runs

- Sprint-assisted runs (resisted or overspeed, cautiously applied)

The Takeaway

Max velocity is about refinement, not force. At this phase, the athlete must be elastic, coordinated, and composed. The 40-yard dash rewards athletes who can build into top speed and hold it cleanly—not just explode out of the blocks.

Posture, rhythm, and precision win the second half of the 40.

Sources

- Mann, R. V. (2013). The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Clark, K. P., & Weyand, P. G. (2014). Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics? Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(6), 604–615.

- Rabita, G., et al. (2015). Sprint mechanics and field 100-m sprint performance in world-class male sprinters. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(11), 893–898.

- Haugen, T., et al. (2019). Sprint conditioning of elite soccer players: Worth the effort or waste of time? Sports Medicine, 49(5), 707–719.

-

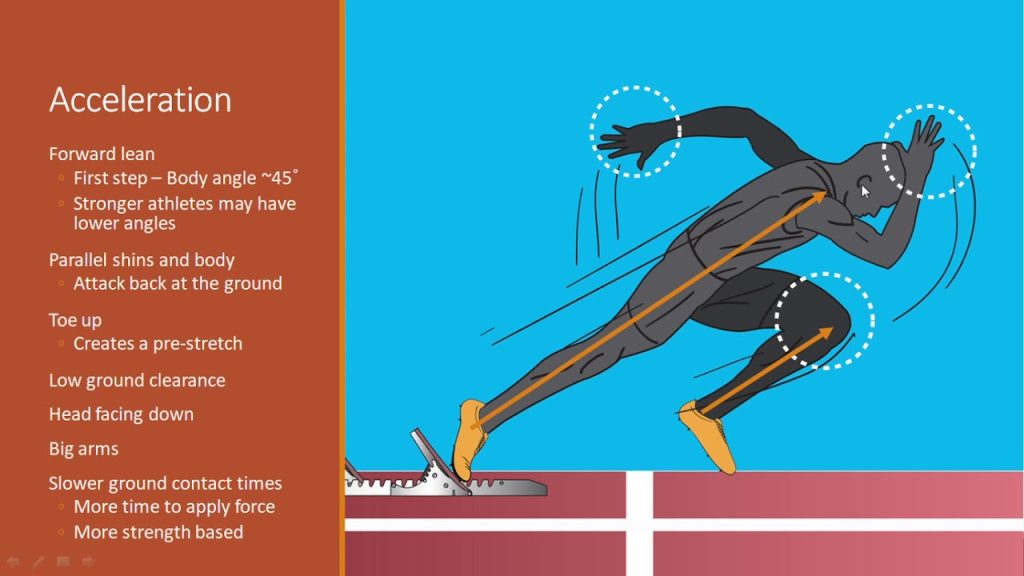

40-Yard Dash – The Essentials: Acceleration

Acceleration is the engine of the 40-yard dash. It’s where an athlete generates momentum, establishes posture, and expresses raw force production. The goal isn’t just to get moving—it’s to do so with precision, power, and posture that builds speed step by step.

In most cases, an athlete will spend 20–25 yards accelerating before reaching their top velocity. This means the acceleration phase isn’t short—it’s half the test.

The Role of the 45-Degree Angle

At the start of the sprint, elite acceleration posture should reflect a forward lean of approximately 45 degrees. This angle:

- Directs force into the ground horizontally

- Maximizes drive and projection

- Keeps the center of mass in front of the base of support

- Reduces vertical force leakage

The torso and shin angle should be parallel in this phase—often referred to as the “power line” in sprint mechanics.

Key Elements of Acceleration Mechanics

1. Body Angle and Lean

Maintain a forward lean that gradually rises over the first 10–20 yards. “Don’t pop up”—staying low allows better push angles and more force transfer.

2. Stride Progression

Early strides should be shorter and more forceful. Stride length increases naturally as velocity builds. Avoid the temptation to open up too soon.

3. Ground Contact

Ground contact time will be longer in early steps (~0.18–0.22 seconds), but should feel powerful and intentional. Each step is a push, not a reach.

4. Arm Drive

Arms remain aggressive, with full-range swings helping to coordinate rhythm and trunk stability. The arms drive down and back in sync with the legs.

5. Foot Strike Position

Feet strike under or slightly behind the hips—not in front. This promotes forward momentum and avoids braking.

6. Postural Control

Head stays in line with spine, eyes down, core braced. Avoid cervical extension (looking up) or lumbar overextension.

Common Acceleration Errors

- Standing upright too early

- Overstriding or reaching out with the foot

- Letting the chest rise before the legs are ready

- Inconsistent rhythm between arms and legs

- Weak initial push due to lack of tension or poor shin angles

Training for Acceleration

Acceleration must be taught and reinforced with drills that emphasize:

- Wall drives and falling starts

- Sled pushes and band-resisted sprints

- Step-count drills to monitor progression

- Force application through split stance and single-leg drive mechanics

- Core integration and trunk stiffness under movement

The Takeaway

Acceleration is not just about effort—it’s about mechanical efficiency under tension. The 45-degree angle isn’t just a posture cue—it’s a launch vector that propels athletes into high-speed movement with intent.

Mastering the acceleration phase will drop 40 times, reduce injury risk, and build transferable speed for any sport.

Sources

- Mann, R. V. (2013). The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Clark, K. P., & Weyand, P. G. (2014). Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics? Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(6), 604–615.

- Wild, J. J., Bezodis, N. E., & Blagrove, R. C. (2023). Sprint start and acceleration performance: A review of biomechanics and training interventions. Sports Medicine, 53, 601–616.

- Rabita, G., et al. (2015). Sprint mechanics and field 100-m sprint performance in world-class male sprinters. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(11), 893–898.

-

40-Yard Dash – The Essentials: The First 10 Yards

The first 10 yards of the 40-yard dash are the launchpad for overall time and top-end speed. This phase is where acceleration is built, mechanics are locked in, and momentum is created. For elite athletes, the quality of these first 5–6 steps often determines whether they hit their peak performance—or fall short.

Why the First 10 Yards Matter

Speed in the 40 is not about maintaining top velocity—it’s about how quickly you can get there. The 0–10 yard segment is where you generate horizontal force and establish your sprint posture.

A poor first 10:

- Delays max speed

- Wastes energy with inefficient steps

- Leads to overstriding or vertical force leaks

- Forces compensation that affects the entire sprint

A great first 10:

- Projects the athlete forward with low, powerful angles

- Uses optimal stride length and frequency

- Minimizes time on the ground and maximizes force into the ground

Step Count Guidelines

- High-level athletes typically reach the 10-yard mark in 6 steps

- Elite sprinters may get there in 5 powerful, efficient strides

Trying to “reach” for distance can lead to overextension, breaking posture and slowing ground contact. Every step should be deliberate, compact, and forceful.

Key Mechanics of the First 10 Yards

1. Projection Angle

Maintain a forward lean of 45 degrees or more in the first 2–3 steps. This angle helps direct force horizontally rather than vertically.

2. Shin and Torso Alignment

The front shin at push-off should match the angle of the torso. This alignment drives momentum forward and avoids energy leaks.

3. Push, Don’t Reach

Each stride should result from pushing off the ground, not reaching forward. Overstriding leads to braking forces and longer ground contact times.

4. Arm Action

Drive the arms aggressively and symmetrically. The arms set rhythm and balance for the lower body. A fast arm equals a fast leg.

5. Gradual Rise

Athletes should not “pop up” in the first few steps. Posture should rise progressively through step 6–10, maintaining low heel recovery and a compact stride.

6. Foot Strike Mechanics

The first steps should be down and back, with the foot striking under or slightly behind the center of mass. Stay away from heel striking or reaching beyond the hip.

Common Errors to Avoid

- Overextension on the first step or two

- Standing up too soon, which kills acceleration

- Crossing over midline with arms or legs

- Passive foot strikes with poor force application

- Lack of rhythm between steps and arm action

Training Focus for the First 10 Yards

To improve this critical segment, integrate:

- Sled or band-resisted sprints

- Step count drills (marking 5–6 steps to 10-yard target)

- Wall drills and falling starts for projection

- Frame-by-frame video analysis for posture and angles

- Bounding or power skips to reinforce stride timing

The Takeaway

The first 10 yards are a technical, neurological, and explosive display of athletic ability. They should be trained with precision, not rushed through. Focus on force, posture, and rhythm—not just speed.

Build the first 10 right, and the rest of the 40 follows.

Sources

- Clark, K. P., & Weyand, P. G. (2014). Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics? Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(6), 604–615.

- Mann, R. V. (2013). The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Murphy, A., Lockie, R., & Coutts, A. (2003). Kinematic determinants of early acceleration in field sport athletes. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 2(4), 144–150.

- Wild, J. J., Bezodis, N. E., & Blagrove, R. C. (2023). Sprint start and acceleration performance: A review of biomechanics and training interventions. Sports Medicine, 53, 601–616.

-

40-Yard Dash – The Essentials: Stance

The 40-yard dash is more than a test of speed—it’s a test of technical execution under pressure. While much attention is given to sprint mechanics, one of the most critical components is the stance. The start determines how effectively force is applied, how quickly an athlete accelerates, and whether they carry momentum efficiently through the sprint.

Why the Stance Matters

The stance sets the tone for the entire 40-yard dash. A poorly set stance—regardless of the athlete’s speed capacity—leads to wasted movement, slower reaction, and inefficient first steps.

An effective stance helps:

- Preload the muscles for explosive output

- Position the center of mass for horizontal drive

- Create tension and stability for rapid movement

- Set up a clean, forceful first step

Key Elements of a Proper Stance

- Foot Placement

- Front foot 1.5–2 foot lengths behind the line

- Back foot staggered behind (approx. 2 feet behind front foot)

- Feet should feel balanced—not flat, not up on toes entirely

- Hand Position

- Lead hand down just behind the line (opposite of front foot)

- Fingers spread for a stable base

- Off-hand loaded and ready to drive with the first step

- Hip and Torso Angle

- Hips slightly higher than shoulders to encourage horizontal drive

- Torso angle aligned with the shin of the front leg

- Chin tucked, eyes down to keep the spine neutral

- Weight Distribution

- Roughly 60–70% of weight on the front foot

- Hips and shoulders coiled to release tension explosively

- Avoid rocking—there should be stillness before the burst

- Mental Cueing

- “Push and punch” – push off the ground and punch the opposite arm

- “Low, long, and loaded” – stay low, take a long first step, and be loaded with tension

Training the Stance

Athletes should not only practice the stance regularly, but also incorporate:

- Isometric start holds (to engrain position and control)

- Video feedback to fine-tune angles and setup

- Band-resisted starts to build tension and force production

- Positional drills focused on explosiveness from a still start

The Takeaway

The 40-yard dash is often won or lost in the first 5 yards. A technically sound stance is not just helpful—it’s essential. It builds the foundation for an explosive, efficient sprint and allows the athlete to express their full speed potential.

Sources

- Clark, K. P., & Weyand, P. G. (2014). Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics? Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(6), 604–615.

- Mann, R. V. (2013). The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Breen, D., et al. (2018). The effect of stance width on sprint start performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(7), 2006–2013.

- Smirniotou, A., Katsikas, C., & Paradisis, G. (2008). The effect of performance level on sprint start and acceleration. New Studies in Athletics, 23(2), 19–27.