Modern medicine has largely been built on biochemistry — hormones, enzymes, neurotransmitters, and pharmaceuticals designed to tweak them. But an increasing number of scientists, researchers, and functional health practitioners are challenging that paradigm.

They’re asking a deeper question:

What if biochemistry isn’t the root… but the result?

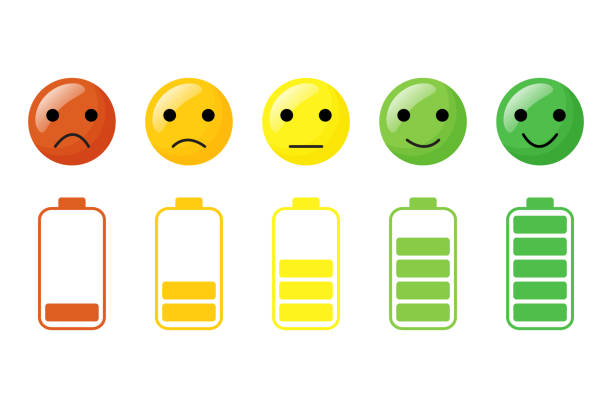

And what if the true root of disease lies in something even more elemental: cellular energy loss?

🔋 The Cell Is an Engine — and Energy Is Its Fuel

Every cell in your body is powered by tiny energy factories called mitochondria. These organelles take in nutrients and oxygen and produce ATP (adenosine triphosphate) — the cell’s energy currency. That energy fuels everything:

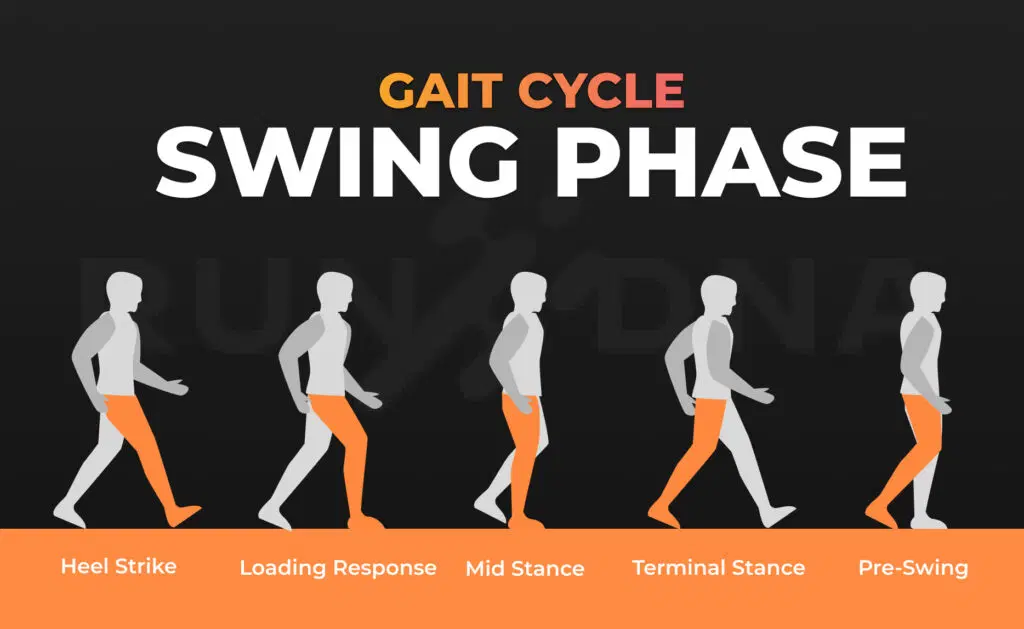

- Muscle contraction

- Brain signaling

- Hormone production

- Immune defense

- Tissue repair

When energy levels drop, the cell can no longer maintain its internal balance — known as homeostasis. And over time, this lack of power can lead to dysfunction, degeneration, and disease.

⚛️ Physics Comes Before Chemistry

Here’s the shift in thinking:

Traditional medicine often starts with chemistry — measuring or manipulating the substances in the body (glucose, cholesterol, serotonin, etc.).

But cells don’t run on chemicals — they run on energy.

Energy governs chemistry.

When a cell is low on energy, the following happens:

- Enzymes stop working properly

- Membranes lose integrity

- DNA repair falters

- Inflammation escalates

- Toxins accumulate

This suggests that the physical state of energy production and transfer is foundational to the chemical reactions that follow. The problem isn’t just biochemical imbalance — it’s bioenergetic failure.

🧬 What the Research Says

Some pioneering scientists are leading this reframing of disease:

🔹 Dr. Doug Wallace (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia)

- Widely regarded as the father of mitochondrial medicine

- Has shown that many chronic diseases — from autism to Alzheimer’s — have mitochondrial dysfunction at their core

- Believes genetics alone can’t explain these diseases, but energy failure can

🔹 Dr. Robert Naviaux (UC San Diego)

- Proposed the “Cell Danger Response” model

- Suggests that when energy drops, cells shift into a protective state that resembles disease

- Believes restoring energy metabolism is key to healing chronic conditions

🔹 Dr. Jack Kruse (Neurosurgeon turned mitochondrial researcher)

- Argues that modern diseases are driven by a mismatch between our biology and environment — especially light, magnetism, and circadian rhythms

- Emphasizes that quantum biology and mitochondrial efficiency are more foundational than genetic mutations

🧠 Implications for Health and Healing

This model shifts our entire approach:

- Instead of asking what chemical is out of balance, ask what energy process has broken down.

- Instead of starting with pills, start with light, movement, breath, and sleep — the foundations of mitochondrial health.

This is why basic habits like:

- Morning sunlight

- Red light therapy

- Deep sleep

- Clean movement and breath

- Eliminating toxins that disrupt the mitochondria

…can have a profound impact on performance and healing — even before we reach for supplements or prescriptions.

🔄 A Return to Root Cause

Understanding disease as an energy loss problem reframes everything:

- Alzheimer’s as “type 3 diabetes” (mitochondrial failure in the brain)

- Cancer as uncontrolled growth in an energetically bankrupt environment

- Autoimmunity as a danger signal stuck in the “on” position

- Even depression as an energetic collapse in neuronal signaling

This isn’t to say biochemistry doesn’t matter — it does. But it’s a downstream effect. Physics — especially bioenergetics — is upstream.

✝️ The Aruka Perspective

At Aruka, we often say that health is not just the absence of disease — it’s the presence of life. And life requires energy.

Scripture says, “In Him was life, and that life was the light of men.” (John 1:4)

When our bodies are aligned with design — when they receive the rhythms, nourishment, movement, rest, and light they were made for — energy flows. Cells heal. Systems recover.

Disease, then, is not just a condition to be managed. It’s a signal — pointing us back to the loss of vitality that begins with energy failure.

And restoring health starts by restoring the source.

📚 Sources

- Wallace, D. C. (2010). Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis.

- Naviaux, R. K. (2014). Metabolic features and regulation of the healing cycle—A new model for chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment. Mitochondrion.

- Wallace, D. C. (2005). A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annual Review of Genetics.

- Kruse, J. (2013–2020). Mitochondrial Series, jackkruse.com

- Nicolson, G. L. (2007). Mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic disease. Integrative Medicine.

- Lane, N. (2005). Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life. Oxford University Press.