As we grow older, most health conversations focus on strength, mobility, cardiovascular fitness, or brain health. But one powerful area is often overlooked—our senses. Sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste, balance, and proprioception (body awareness) all subtly decline with age. This decline can directly affect our safety, independence, and quality of life.

Here’s the good news: just like your muscles and brain, your senses can be trained. And doing so may be one of the most underrated strategies for staying sharp, stable, and engaged as you age.

WHY SENSORY HEALTH MATTERS

Your senses are the gateway between your body and the outside world. They help you avoid danger, stay upright, enjoy your meals, and communicate effectively. When sensory systems decline:

- Falls become more likely due to reduced depth perception, balance, or hearing.

- Cognitive decline can speed up—research shows that poor sensory input affects brain health.

- Daily enjoyment suffers, from muted tastes to difficulty hearing conversations.

You don’t have to accept this as normal aging. You can train your senses.

SIMPLE WAYS TO TRAIN EACH SENSE

1. VISION

- Track moving objects with your eyes to build coordination.

- Shift your focus from near to far to improve flexibility.

- Get more natural light and rest your eyes from screens.

- Practice figure-8 or diagonal eye movements.

2. HEARING

- Practice sound recognition—sit quietly and name the sounds you hear.

- Try selective listening drills in noisy environments.

- Avoid constant loud noise and use noise-canceling headphones when needed.

3. TOUCH

- Use different surfaces (grass, gravel, sand) barefoot to stimulate foot nerves.

- Roll textured balls in your hands to sharpen tactile feedback.

- Contrast hot/cold showers to stimulate the nervous system.

4. SMELL & TASTE

- Smell herbs or spices blindfolded to increase discrimination.

- Eat slowly and try to identify individual ingredients.

- Rotate your food choices to expose your senses to variety.

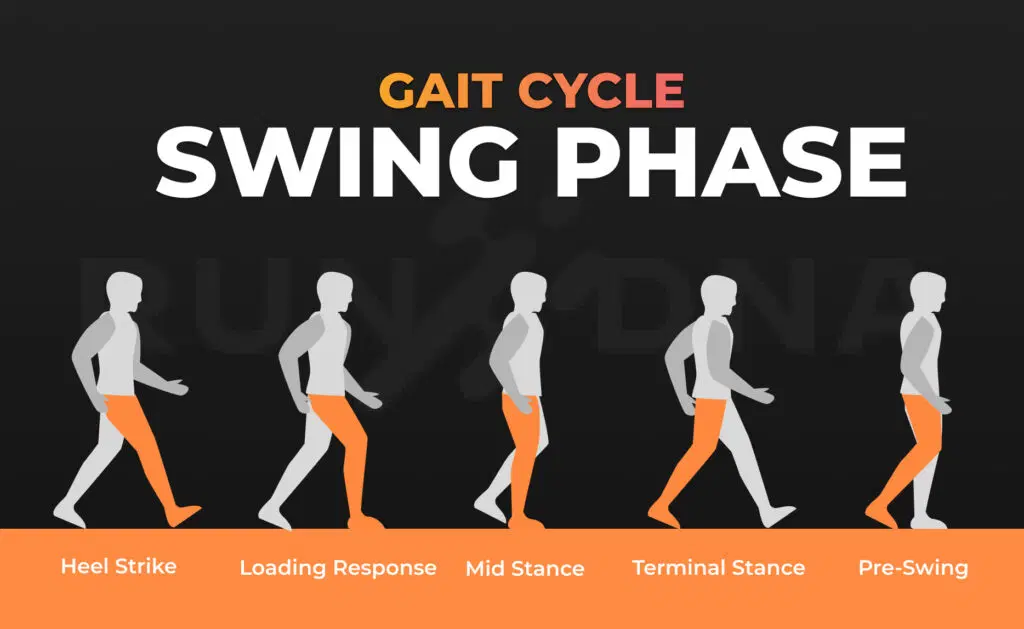

5. BALANCE & PROPRIOCEPTION

- Practice standing on one foot or walking on uneven ground.

- Use stability pads or wobble boards to challenge joint awareness.

- Include closed-eye balance drills for extra sensory engagement.

THE BRAIN-SENSE CONNECTION

Your senses don’t operate alone—they’re connected to your brain and nervous system. Every sensory drill strengthens your brain’s ability to interpret information, stay alert, and respond quickly. Sensory training is brain training in disguise.

INTEGRATE IT INTO YOUR DAILY LIFE

- Add 3–5 minutes of sensory drills to your warm-up or morning routine.

- Use your non-dominant hand for daily tasks to activate new brain areas.

- Take “sensory walks” where you focus on sights, sounds, and smells.

- Eat meals without distractions to fully engage taste and smell.

FINAL THOUGHT

Aging doesn’t have to mean fading.

Honing your senses can help you stay stable, sharp, and connected to the world around you. It’s a simple but powerful way to support your health, independence, and brain as the years go by.

Train your senses—because what you don’t use, you lose.