Acceleration is the engine of the 40-yard dash. It’s where an athlete generates momentum, establishes posture, and expresses raw force production. The goal isn’t just to get moving—it’s to do so with precision, power, and posture that builds speed step by step.

In most cases, an athlete will spend 20–25 yards accelerating before reaching their top velocity. This means the acceleration phase isn’t short—it’s half the test.

The Role of the 45-Degree Angle

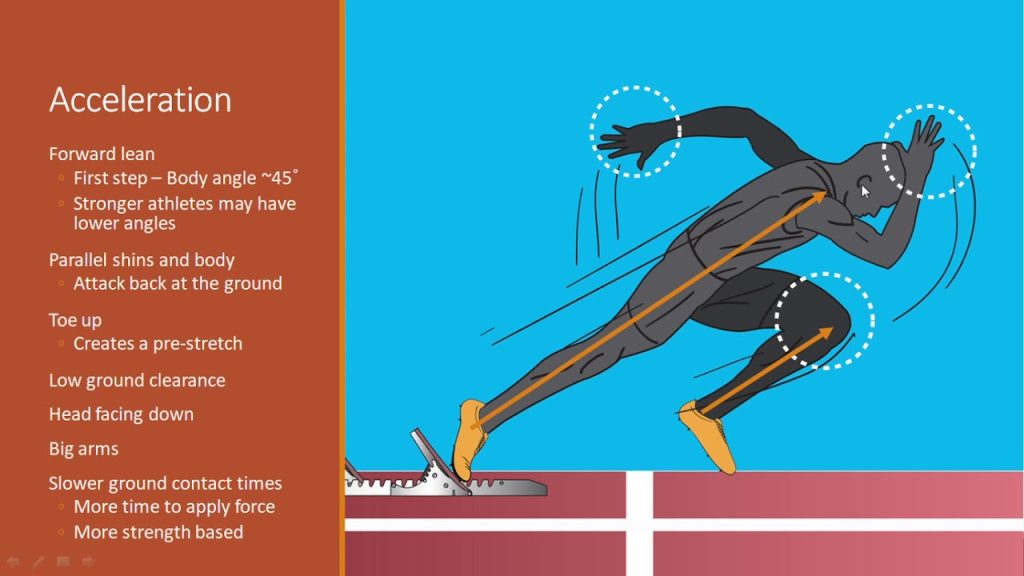

At the start of the sprint, elite acceleration posture should reflect a forward lean of approximately 45 degrees. This angle:

- Directs force into the ground horizontally

- Maximizes drive and projection

- Keeps the center of mass in front of the base of support

- Reduces vertical force leakage

The torso and shin angle should be parallel in this phase—often referred to as the “power line” in sprint mechanics.

Key Elements of Acceleration Mechanics

1. Body Angle and Lean

Maintain a forward lean that gradually rises over the first 10–20 yards. “Don’t pop up”—staying low allows better push angles and more force transfer.

2. Stride Progression

Early strides should be shorter and more forceful. Stride length increases naturally as velocity builds. Avoid the temptation to open up too soon.

3. Ground Contact

Ground contact time will be longer in early steps (~0.18–0.22 seconds), but should feel powerful and intentional. Each step is a push, not a reach.

4. Arm Drive

Arms remain aggressive, with full-range swings helping to coordinate rhythm and trunk stability. The arms drive down and back in sync with the legs.

5. Foot Strike Position

Feet strike under or slightly behind the hips—not in front. This promotes forward momentum and avoids braking.

6. Postural Control

Head stays in line with spine, eyes down, core braced. Avoid cervical extension (looking up) or lumbar overextension.

Common Acceleration Errors

- Standing upright too early

- Overstriding or reaching out with the foot

- Letting the chest rise before the legs are ready

- Inconsistent rhythm between arms and legs

- Weak initial push due to lack of tension or poor shin angles

Training for Acceleration

Acceleration must be taught and reinforced with drills that emphasize:

- Wall drives and falling starts

- Sled pushes and band-resisted sprints

- Step-count drills to monitor progression

- Force application through split stance and single-leg drive mechanics

- Core integration and trunk stiffness under movement

The Takeaway

Acceleration is not just about effort—it’s about mechanical efficiency under tension. The 45-degree angle isn’t just a posture cue—it’s a launch vector that propels athletes into high-speed movement with intent.

Mastering the acceleration phase will drop 40 times, reduce injury risk, and build transferable speed for any sport.

Sources

- Mann, R. V. (2013). The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Clark, K. P., & Weyand, P. G. (2014). Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics? Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(6), 604–615.

- Wild, J. J., Bezodis, N. E., & Blagrove, R. C. (2023). Sprint start and acceleration performance: A review of biomechanics and training interventions. Sports Medicine, 53, 601–616.

- Rabita, G., et al. (2015). Sprint mechanics and field 100-m sprint performance in world-class male sprinters. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(11), 893–898.

Leave a Reply